Karl Zong

In Gallery 0 on the first floor of the West Bund Museum in Shanghai, a series of geometric forms, either full or empty, are visible. Flat panels with wooden textures and Oxford fabrics with industrial roughness — they construct red cubes, olive green cones, or black and white spheres rising from the floor, and metal pipe fittings forming various frames. Following the planes of color taped to the floor as we wander through the gallery, the volumes shade and conceal each other, creating a variety of abstract forms.

These geometries with almost Constructivist origins are part of artist Nabuqi’s latest project named “Everything goes back to square one”. The key mediums of her practice are sculpture and installation, illustrating Heideggerian philosophy in the dimensions of visual phenomena and spatial perception, respectively. For Venice Biennale 2019, Nabuqi’s two monumental installations— the intricate and detail-filled “Do real things happen in moments of rationality?” and the ironically tilted billboard “Destination”— tackle the complex relationship between fiction and reality.

Around the end of 2021, in an alternative space converted from a residential apartment in Shanghai's Jing'an district, Nabuqi has just presented a project entitled "Ghost, Skin, Dwelling". For this project, she set up objects between being seen and being used in a nearly rough room, introducing an unprecedented intimacy between body and object. Last year's deep exploration of habitats and domestic space inspired Nabuqi to engage in retrospective thinking, in a sense. For this project at the West Bund Museum, the field of discussion is shifted back to the public space of functionality.

DISORIENTATION—GAME

For Nabuqi, it is the atmosphere that is the most significant feature of a space, through which scenic, sequential experiences are presented to the viewers. This line of thinking is absolutely phenomenological. Despite the site-specificity of the project in the first place, the artist doesn’t rely exclusively on the exhibition space itself. Nabuqi poetically elucidates the window of the gallery: “it is not completely transparent, but with its opening, a sense of connection with its exteriors is established, allowing for filtered and softened natural light to come through.” Her works are ideated accordingly to the specific environment, but the environment is never the starting point. A balance is needed between the characters of a work and its relationship with its surroundings.

Located in the Xuhui Riverfront area, West Bund Museum is fairly close to a popular public urban space full of greeneries, waterscapes, and skate parks. What we see at the exhibition can be easily but subtly linked to the outdoor playground not far away. Uncanny objects and alien references fill this white box. The abrupt corporeal appearance within the gallery is encountered with an acute sense of disorientation.

This disorientation represents a pivotal moment in Sarah Ahmed’s “queer phenomenology”. Surrounded by the neutral white walls and the well-configured lighting, these quasi-architectural installations appear peculiar and queer (in the original sense), making a cut in ordinary display norms of art institutions. Having lost their way, the subjects instinctively attempt to escape this derailment, progressively re-orienting themselves by re-adjustments and re-shaping to reside in this time-space once again. Experiences within this gallery are similar— with the fascination of these oddities eventually fading out, we regain perceptual control over the space with the eyes of the body adapting to the heterogenous existence.

The gallery resounds with innocent laughter as kids come in. Indeed these vibrant colors and fundamental geometries are reinforcing their kinship to kids’ activities. They spontaneously interact with the structures, suggesting an alternative way to perceive the space. They climb into the cube shelter made of wood, walk across the slopes in the middle or touch the metal tubes. They ducked into a conical chamber assembled from Oxford cloth, a "meditation room" suspended by nylon ropes in a pyramidal frame with a circular base plate repeatedly defining two areas. They climbed up from the floor to the spherical crown-like volume, sitting or standing, overlooking the entire exhibition. Until this moment, the space is truly activated as a place to be described.

Without hesitation, Nabuqi mentioned Isamu Noguchi’s influence in making her work. As a prominent Japanese-American sculptor, Noguchi is also known for creating playful spaces for kids, which are named by himself “playscapes”. For Nabuqi, Noguchi’s practice of this sort seems utopian, but the vision is shared nonetheless.

Yet, Nabuqi’s version of utopia is more neutral and pure, compared to Noguchi’s emphasis on educational didactics. The relationship between the installation and mundane everyday objects is obscured, shifting between the two poles of abstract and representational. The dichotomy of privacy and publicity is placed into multiple layers, constantly erasing and coagulating the preconditioned boundaries. A playful field of chaos emerges.

Free from all preconceptions of order, a pure spatial experience brings us back to “square one”. The title of the exhibition raises new questions: what is “square one”? Did anything end before the “square one”? All of this implies an interstitial tense, a tense that resides in the present but is infinitely open to the before and after.

IMAGINATION—CONTINGENCY

Any attempt to categorize the objects in the gallery will face failure. The elements of sculpture and installations intertwined with each other to form a whole. For the artist, this is creative progress. Looking back to the early days, Nabuqi recalls being only capable of working on one thing at a time, whereas right now the mishmash of disparate elements can lead to a more open-ended output. What she creates in the gallery has no set path and is not arbitrary.

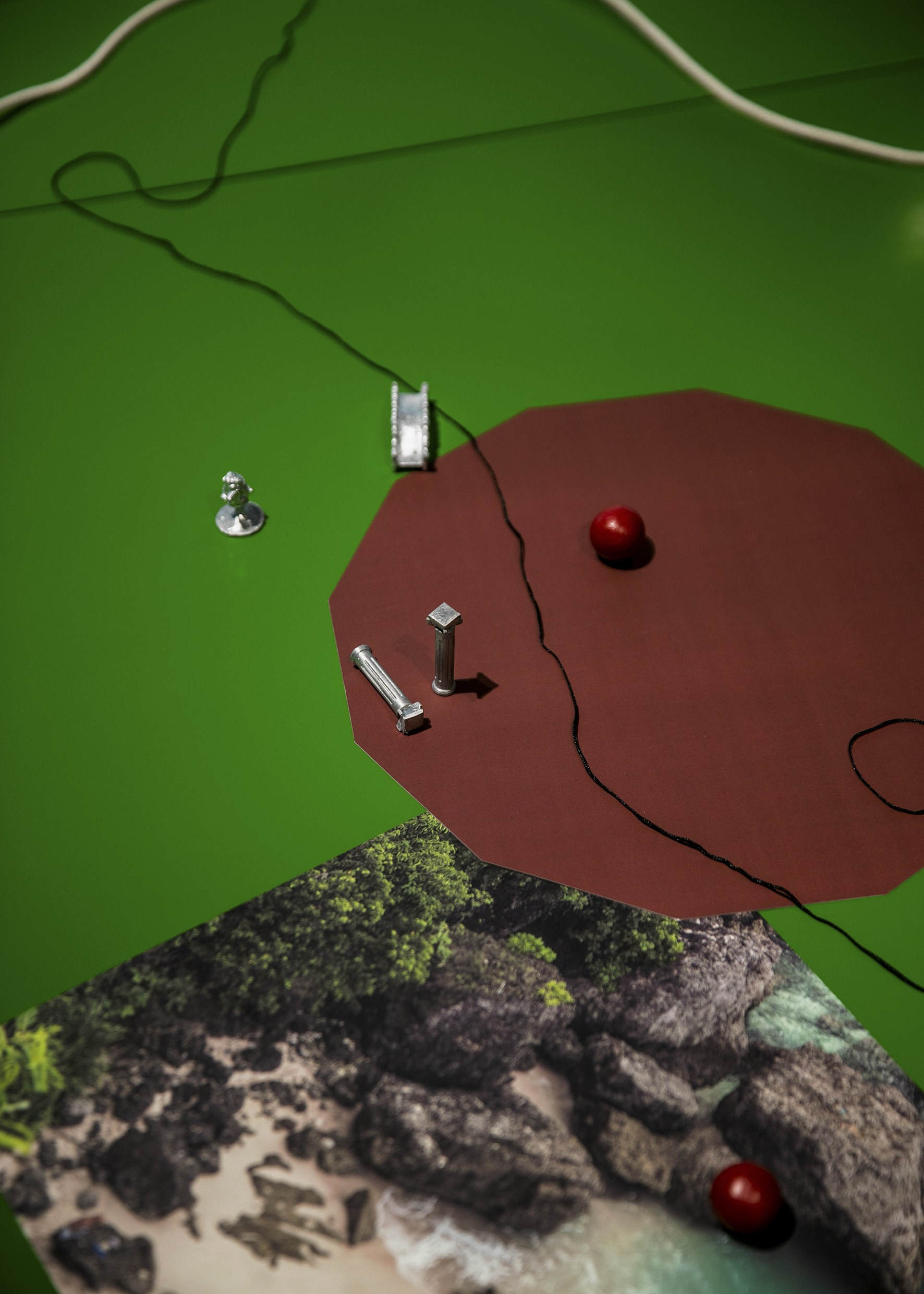

Nabuqi uses language in a way that words are almost seen as objects. The works are titled in a self-evident manner, “Hybrid structure”, ”Meditation room”, and ”Upslope”. Three nouns are only stating the truth, reluctant to reveal any additional information. As we go deeper into the space, the display of the exhibition ends at a zig-zagging table, with trinkets splattered across the surface. We see minuscule models of buildings, pavilions, pieces of furniture and trees made of alloy, small pieces of colorful geometries, and pictures of landscapes printed on paper. All of this is constantly in flux, never reaching an end. The installation is like an extreme abstraction of the world, with the fluid uncertainty flowing through the gaps for interpretation.

These objects might evoke a certain resemblance to Nabuqi’s previous works. They relate to objects and elements that would be found in urban public spaces, or they are symbols like arrows and orbs and found images of natural landscapes. These motifs recur in Nabuqi’s recent works. Several years ago the artist treated them separately: “sculptures are sculptures, while installations are combinations of found objects.” Yet from last year, the distinction between different media of sculpture and installation seems to have melted away.

Compared to all the other installations in the exhibition, the events on this tabletop are taking place on a more profound level— objects are assembled on three levels. The table itself forms a landscaped environment - from other installations that focus on the experience of the body approaching here, perception is withdrawn from the physical into the psychological interior, and imaginative engagement is encouraged. The objects move in different directions, whereas different materials, forms and textures reside equally on the table. They can be freely arranged and combined by the viewer, not dissimilar to the Sims game.

This one is called “Board game: accidental cases”, with reality supplemented by its own description. The complex forms of the table installation don’t promise intentions or endgames in any precise sense. It is a private game constructed by the artist without any rules. When the Frenchman Georges Bataille spoke of the monumentality of the architecture and sculptures in the last century, he was criticizing the increasing power of these art forms and the symbolic dominance of the hierarchical and patriarchal norms of the social order. From this perspective, Nabuqi’s ambiguous gaze towards sculpture/installation is almost a gesture of transgression.

It is well known that the archetypal modern museum is the cabinet of curiosities, “to be only viewed from afar but never to be toyed with.” But here the participation or intervention from the audience is given its deserved attention. The emergence of meaning also relies upon everyone who tried to establish a connection to the objects. The right to create is given back to the audience. They re-organize the objects according to their own memories and likings, exploring the one situation that matters the most.

The active contribution from the audience is evident in the WeChat mini program specially designed for the work. Audiences are encouraged to upload photographic documentation of their playing with the installation. So there we have an abundance of images. Each one of them is a metaphoric landscape, containing personal traces and plots. The miniature world of abstractions opens up a world of entropy. The lightness of Nabuqi’s strategies almost trespasses the impenetrable correlation between subjects and objects, echoing the assertion made by the speculative realist Quentin Meillassoux— the only definite thing in the world is chance.

In fact, we don’t really have to establish an overly radical standpoint for Nabuqi. Let’s just listen to her own voice: ”everything goes back to square one.” Square one contains her persistent focus on volumes and spaces from the beginning of her experiences with sculpture. This purity is like the primitive state of a playground. Her fundamental vision is to bring joy to the audience with her works, leading us to “a state of goodwill, equality, and comfort.” In the now of drastic turmoils, this can actually be our better future.

This article was originally published in KINFOLK, Autumn 2022 (Issue 45).